![]()

![]()

Headingley Karate

|

|

|

Kyusho-Jutsu

Kyusho is a Japanese word that roughly translates as vital point or tender spot. It can also translate as secret. Kyusho-jutsu then, is the name generally given to the art or skill of attacking the (sometimes secret) vital points, usually by striking them. The associated skill of seizing vital points (rather than striking them) is often called tuite. These concepts also exist in Chinese (and other) martial arts where they are termed Dim Mak and Chin Na respectively.

But what exactly are the kyusho points? And can they really be used in self-defence?

There are two competing schools of thought on what vital points are and why they work. Some people call them pressure points and consider them to be the same pressure points that are used in acupuncture and other branches of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Others use Modern Western Medicine to guide them to useful points and explain why they work.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

Acupuncture recognises some 360 or so classical tsubo (‘acu-points’) plus a few more non-classical points. The classical points are considered to be connected by meridians, lines of energy within the body. An acupuncturist stimulates the tsubo in different ways in order to affect the patient’s qi (chi), or ‘internal energy’. Many martial artists now use the same ideas, not just attacking the tsubo themselves but also using the theoretical models of TCM to explain why it works. However, there are several flaws in this approach:

- Some tsubo are certainly martially useful as vital points. Many though are not. And some of the most useful vital points aren’t actually tsubo at all. In an attempt to make reality fit the model some martial artists even give martially useful points the names of nearby tsubo. The classic example for me is the tsubo known as Lung 5. The real Lung 5 is in the elbow crease. However, almost without exception martial artists ignore this point (which isn’t martially very useful) and instead give the name ‘Lung 5’ to a point an inch or so down the forearm. This point is not a tsubo, but it is a kyusho, ie. a martially useful point.

Quite often I hear martial artists refer to the science of TCM, or the laws of five elements, the rule of ‘fire melts metal’, quadrant theory and so on. I believe this demonstrates a complete misunderstanding or misrepresentation of what TCM is about. People mistakenly imagine qi to be like water running through a pipe, or electricity through a wire, the tsubo’s being valves or reservoirs where you can block or redirect the flow. This is a mechanistic model, in which activating a particular ‘valve’ always has the same outcome. It is applying modern scientific ideas of causality, ie. the same cause will always produce the same effect. Unfortunately its applying it to a system of thought which evolved in a culture that had embraced neither science nor causality in the way that we would understand them today. The practitioner of TCM is an artist, not a scientist, drawing on experience, intuition and often more than one different theoretical model in order to help their patients. If one model doesn’t appear useful, they can simply switch to another, they don’t worry about why the first model didn’t work. This approach is unthinkable from a scientific point of view, science must by definition be consistent. TCM is not a scientific model. Instead it can be thought of as a ‘framework on which to hang your intuition’ or, as my partner (like me, she fully qualified as a practitioner of Shiatsu and Oriental Medicine) eloquently put it, a ‘collection of suggestions’ for improving health. So we can see that using TCM to explain or predict the effect of attacking a particular point, or series of points, is a concept that is fundamentally flawed. It is not predictive in that sense.

Quite often I hear martial artists refer to the science of TCM, or the laws of five elements, the rule of ‘fire melts metal’, quadrant theory and so on. I believe this demonstrates a complete misunderstanding or misrepresentation of what TCM is about. People mistakenly imagine qi to be like water running through a pipe, or electricity through a wire, the tsubo’s being valves or reservoirs where you can block or redirect the flow. This is a mechanistic model, in which activating a particular ‘valve’ always has the same outcome. It is applying modern scientific ideas of causality, ie. the same cause will always produce the same effect. Unfortunately its applying it to a system of thought which evolved in a culture that had embraced neither science nor causality in the way that we would understand them today. The practitioner of TCM is an artist, not a scientist, drawing on experience, intuition and often more than one different theoretical model in order to help their patients. If one model doesn’t appear useful, they can simply switch to another, they don’t worry about why the first model didn’t work. This approach is unthinkable from a scientific point of view, science must by definition be consistent. TCM is not a scientific model. Instead it can be thought of as a ‘framework on which to hang your intuition’ or, as my partner (like me, she fully qualified as a practitioner of Shiatsu and Oriental Medicine) eloquently put it, a ‘collection of suggestions’ for improving health. So we can see that using TCM to explain or predict the effect of attacking a particular point, or series of points, is a concept that is fundamentally flawed. It is not predictive in that sense.

- Quite simply, there is no actual evidence of the value in TCM as a model for understanding kyusho-jitsu. The only real research that I am aware of that has been done in this area was conducted by Dr Zoltan Dienes, an experimental psychologist at Sussex University, and myself. Despite a series of experiments to investigate the use of TCM in kyusho-jutsu we could find no supportive evidence (click here for details of these experiments).

In conclusion then, using TCM to explain and understand kyusho-jutsu is simply a misuse of the ideas of TCM, has no empirical evidence to support it and is usually is at odds with the way that people actually train (eg. hitting the wrong ‘Lung 5’ point and ignoring the real one).

Modern Western Medicine (MWM)

MWM attempts to explain kyusho in terms of stimulation of the nervous system and the effects of anatomical or physiological damage. The nervous system can be manipulated to produce a variety of well understood reflexes. The central nervous and vascular systems can be attacked directly (or even indirectly) to produce unconsciousness. Trauma to the abdominal and thoracic organs can cause longer term damage. All of these ideas can be fairly well tested for and verified. The reflexes are real and readily reproducible. The central nervous system can be monitored whilst different stimuli are applied and the effects measured. And there is plenty of medical evidence of the effects of trauma on the internal organs (Bruce Miller has published some interesting work explaining ‘delayed death touches’ in anatomical and physiological terms). Knowledge of anatomy can enable the diligent student to find kyusho points that there were not previously aware of. Given, for example, that one kyusho might be found at a point where a nerve lies over a bone (so it can be compressed against the bone) the student can search the body for other similar areas, then test them to see how well they work and what effects they produce.

I don’t believe that the evidence for the MWM approach is absolutely watertight. It’s pretty good, but it doesn’t explain every aspect of kyusho-jutsu. Given how much it does explain though is good evidence that the model is fundamentally sound. We just don’t yet understand the human body well enough yet to have a cast iron explanation of every aspect of it. But it seems clear that this will come with time, without any need to rewrite the scientific model in any major way.

A personal view

A single-knuckle strike to the sternum

|

My own definition of kyusho is simple: they are points that, if attacked correctly, produce an effect that is out of proportion to the stimulus. To be more specific, the effect is disproportionately large relative to the stimulus (after all, I wouldn’t want to achieve a disproportionately small effect).

Let us look at an example. If I was to punch an aggressor lightly in the face it would have little effect. If I punch a bit harder I might manage to bruise or cut the skin of the face, or to knock the person backwards a little. Harder again and I might even manage to knock them out. Really increase the force and its just possible that I might manage to break bone. This would require an awful lot of force and might well damage my fist in the process. Obviously this is not a pressure point attack. So instead, let’s poke the person in the eye! This could be done with as little force as my first blow but produces a much more dramatic result. The victim will jerk away reflexively drawing their hands towards their eyes, their eyes will tear up, their vision will be impaired (possibly permanently) and they will likely be distracted by the intense pain. This surely then qualifies as a ‘pressure point’ attack – the effect is very impressive and totally out of proportion to the small amount of force used.

Mechanism (How and Why)

The eye-poke is a simple and obvious technique but is actually a good example of a vital point strike. The effect is certainly out of proportion to the force of the attack, but lets look at why that is.

- Firstly, its very painful. Its obviously a good thing to cause an attacker pain. It may put them off continuing the attack, or it may distract them from what you’re about to do the next. It certainly gives you the initiative. However, pain cannot be relied on in itself. Pain can be mentally blocked or ignored, some people just don’t feel it as much, and the effect of alcohol or drugs can reduce its intensity.

- A series of physiological reflexes have been triggered by the stimulus of a foreign body entering the eye.

- The head jerks back out of the way, to remove the eye from the stimulus. If the stimulus is strong or fast enough the whole body will join in to help remove the eye from danger.

- The hands come up to push the foreign body away.

- The eyes blink – most likely repeatedly.

- Both eyes tear up – tears can help to remove any remnants of a foreign body still in the eye.

As a result the attacker is distracted, suffers a loss of balance, momentarily ceases their attack, and has one of their senses (sight) impaired. Not bad for a technique that took virtually no strength to apply.

It should be understood that the reflexes mentioned here are involuntary. The conscious mind does not play a part in them. Due to the way the nervous system works the conscious mind is only informed about such actions during or while they are taking place. So you can’t choose not to react – unless you knew beforehand exactly what was going to happen, in which case it is possible to consciously over-ride the reflexes to some degree.

Of course, some will argue that the eye is not a kyusho. Its too obvious, everyone knows about it, there’s nothing secret or mysterious about it, etc. I’ve chosen to discuss this point simply because it is a clear example of how striking a specific point can cause pain and dysfunction (or damage), and produce involuntary, predictable reflexes. There are quite a number of other, rather less obvious kyusho. The methods of attack may vary but they should all produce some combination of the same effects, ie. pain, dysfunction and/or involuntary reflexes.

OK, so now we have definition of what kyusho are, and a little insight into how and why they work. But can they be used for real? Many people have come up with all sorts of objections to the use of kyusho. Some objections are reasonable and well thought out, and therefore worthy of addressing. The objections generally fall into one of the two following categories.

Its too difficult

Even if it misses the kyusho point, a knee strike to the thigh works well

|

Kyusho are too small, too hard to hit in the chaos of real violence, they don’t work on everyone, the theory is too complicated etc. Well the last objection is easy to dismiss. TCM theory has been shown to be irrelevant, all you need to know is where and how to hit, and that just requires lots of practice. Intellectual study can inform the way you practice, but it simply isn’t necessary to engage your intellect mid-combat. It is true however, that kyusho can be quite hard to hit. But they’re not actually as small as the TCM model suggests. Some cover a reasonably large area. Others can be better thought of as zones or lines rather than specific points. So that makes them easier to hit, if you’ve practiced the correct way to do so. It also helps if you ‘set-up’ attacks to kyusho points. Some people think that ‘set-up’ means something mystical and ‘energetic’, but that’s not what I mean. Rather, you create the opportunities to attack the kyusho. For example, as an attacker throws a punch you must either be very lucky or exceptionally well skilled to hit a specific kyusho on their body, which is a moving target, whilst simultaneously blocking or evading their punch. So initially I would suggest a rather more ‘broad brush stroke’ technique – block with one hand and palm-heel to the face with the other. Now you’ve unbalanced the attacker and distracted them. Immediately follow this by grabbing or otherwise capturing their arm and you’re starting to control their movements (and where they are in relation to your body). Having momentarily gained a degree of control its now much easier to hit a more precise target. But what if, despite all your efforts, you miss anyway? Easy, don’t rely on the kyusho. There’s no need to give up on the rest of your martial skills just because you’ve discovered kyusho. A strong punch is still a strong punch. If it hits a kyusho all the better, if it misses it should still have an effect. This is the principle known as ‘redundancy’ in Ao Denkou Jitsu - a technique should still work mechanically irrespective of whether you fail to get an effect from a kyusho point.

So there are ways of increasing the likelihood of successfully striking kyusho. It should be noted though that this will have an effect on your whole martial art. It is not sufficient to simply learn the location of a few kyusho and aim for those with the standard long range techniques of modern Karate (or Taekwondo, or Kung Fu, or whatever modern long range art form). You have to learn to be stick to the opponent, to disrupt their balance and to control their movements – skills and techniques not generally a part of the modern striking systems.

Kyusho aren’t part of Karate

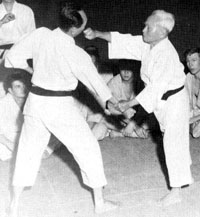

Funakoshi demonstrating a single knuckle strike to a vital point

|

Or an even bolder idea: Kyusho don’t exist! This seems so preposterous to me as to be hardly worth addressing, yet there are people who maintain this view. It is essentially equivalent to doubting the existence of the human nervous system, human reflexes and even a phenomena we can see on our television screens almost any day of the week – boxers knocking each other unconscious by punching the jaw.

Thinking that kyusho are nothing to do with Karate, however, is quite an understandable mistake to make. You might ask: if kyusho-jutsu is a part of Karate, why isn’t it in our syllabus? Why isn’t everyone doing it? Quite simply, Karate (and other related striking systems) was dramatically modified over the course of the 20th century. 21st century Karate is usually very, very different from its 19th century ancestor. A number of aspects of the art were simply dropped by the teachers of the time, who considered that they were not relevant to a modern society. It is entirely understandable that the modern practitioner has very little knowledge of the history of their art. I could cite numerous examples of Okinawan Karate systems that have kept parts of this knowledge alive. But instead I will leave the explanation to Gichin Funakoshi, widely considered to be the father of modern Karate. In his 1925 book Rentan Goshin Karate Jutsu, Funakoshi wrote:

“The reason that until now there has been no assigning of ranks in karate is that it has not been possible to have shiai (competitive matches) as in judo or kendo. This is because of the devastating power of karate techniques; a strike to a vital point could immediately prove fatal…With continuing research it is not unfeasible that as in judo and kendo our karate too, might incorporate a grading system through the adoption of protective gear and the banning of attacks to vital points.”

Conclusion

Kyusho-Jutsu is an integral component of the older systems of Karate. If you are interested in self-defence then it seems wholly sensible to learn to attack the vulnerable parts of an assailant's body. This way you can maximise your chances of surviving unharmed. Being skilled in attacking kyusho doesn't mean that you don't have to bother about power generation, good mechanics and so on. It doesn't replace the other skills developed by Karate practice, it simply builds upon them.

If you want to learn more about this area of Karate training then you really need to find a good school. But be wary of who you train with. There are many charlatans who just wish to part you from your money, in return for teaching you meaningless mumbo-jumbo. Have a good look around at what tuition is available, and try to keep your feet firmly on the ground!

To learn more about our approach to Kyusho Jutsu, come along for a FREE trial lesson.